The time I noticed how different people can be.

I don’t often write about my father’s side of the family. The simple reason is that I didn’t know them very well. We didn’t spend much time with them as children. I can probably count on one hand the number of times I saw my grandmother, Johanna.

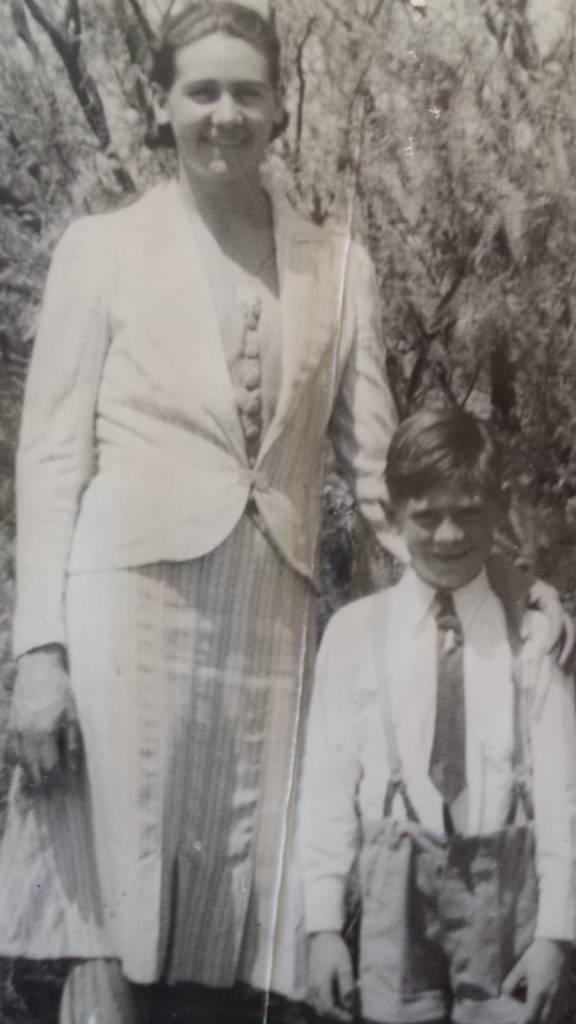

We called her Ouma Dee. She was an extremely strict, authoritarian woman. Even her stiff, upright posture spoke of her no-nonsense approach to life. Everything about her was neat and orderly – her hair, her clothes, her house – but she lacked warmth and kindness. She married three times, and I don’t think she ever considered her own children when choosing her next husband. My father suffered greatly at the hands of her second husband.

The only thing I shared with her was a name. My parents thought it a good idea to name me after her – luckily, that was the only thing we had in common.

This story, though, is about Ouma Dee’s sister – Tannie Braam, her husband, Oom Martiens, and their granddaughter, Braampie. My dad lived with them on their farm in the Kalahari for a time when he was a teenager, simply because his stepfather didn’t want him in the house.

It must have been around December of that year because we had already moved to the city when my dad received a call from Oom Martiens. They were in Bloemfontein and wanted to stop by for tea. Mum and I tidied the house, dusted the sitting room, and puffed up the cushions.

When they arrived, Tannie Braam climbed out of the car carrying three white plastic bags, bulging at the sides. As I bent down to greet her, I immediately caught the smell of hot chips, vinegar and fried fish. In the 80s, fast food was a real treat for us, and we rarely bought it. My mother cooked everything from scratch, and if we wanted something sweet, we baked a cake, and we always had grandmother Soes’s ginger biscuits.

They walked straight into the kitchen and sat down at Mum’s red Formica table. My mind was already racing ahead, imagining the taste of those chips.

Before Mum could fetch plates or cutlery, Tannie Braam tipped the bags onto the table. They began eating immediately. There were sandwiches, fish, chips, battered sausages, Saveloys and sausage rolls – a small mountain of food. They didn’t wash their hands. And they didn’t offer any to us.

I stood leaning against the kitchen cupboard, feeling slightly weak. I remember watching Oom Martiens’ head and shoulders moving as he ate – the way ducks do in the park when they’ve had too much bread. For a moment, I thought he might stop, but he didn’t.

When they had finished every oily scrap, Tannie Braam wiped her hands and mouth on the empty chip paper and brushed pastry flakes from her ample bosom. Oom Martiens leaned back with a satisfied grunt and said:

“Hannalise, can you make us a cup of black tea and add two ice cubes?”

I stared at him. In my head, still filled with images of sausages and chips, a swear word formed and nearly escaped my mouth. Instead, I pushed myself away from the kitchen cupboard and walked slowly down the hallway and slammed the door to my bedroom shut with force.

It’s strange how something so small stays with you. Nothing truly important happened that day. But perhaps it stayed because of the contrast, the way we were raised to share what we had, or because of the generosity and quiet care of my Ouma Soes and Oupa Piet, who gave so freely and never asked for anything in return.

Leave a comment